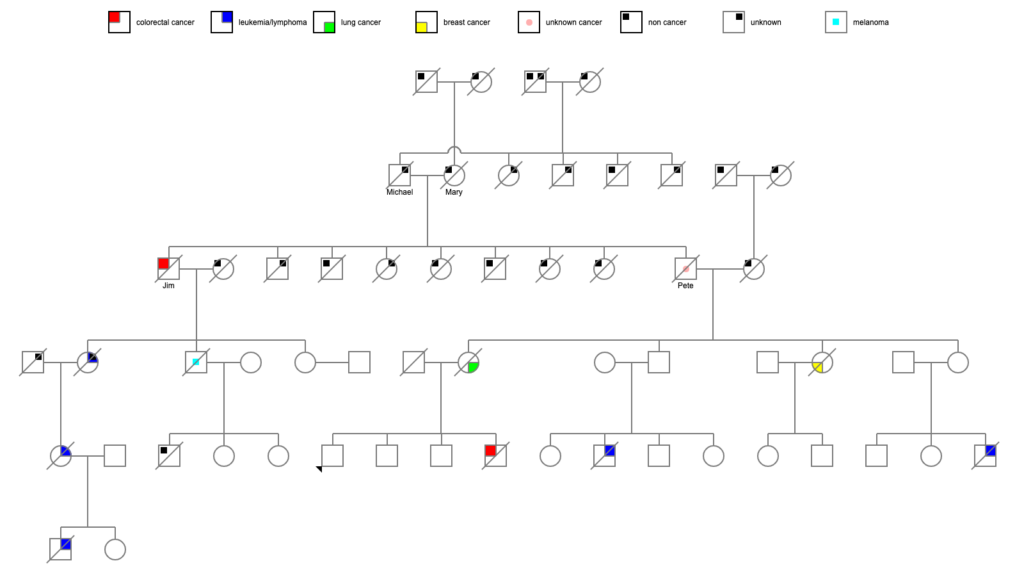

I’ve been MIA for months now, primarily because my father started showing signs of illness in March 2023, ended up in the ER on May 3rd, and passed away on July 3rd. Wrangling with my own grief (starting after his diagnosis of aggressive lymphoma), the aftermath of his relatively sudden departure, and helping to pick up the pieces of my mother’s life has consumed me for 5 months now. We’re still in the midst of it, really. But one of my cousins suggested I post the eulogy I gave at my father’s funeral — months ago now, on July 12th — and I finally have the energy to do it, in part because today is my parents’ 60th wedding anniversary. We all told Mom it was okay to round up and say they had been married 60 years.

Charles John McLaughlin III (Jack) (14 May 1931-3 July 2023)

Our McLaughlins are tale-tellers and family historians, and so we know the value of stories as bricks in the edifice of memory. Stories are what everyone uses to build their own mythology of a given person – mythology not in the sense that the stories are not true, but in the sense that this conglomeration of stories by necessity represents only part of the truth of that person.

Today, I’m not going to recite Dad’s life story as I know it. Instead, I would like to share a few of my own favorite building block stories about him.

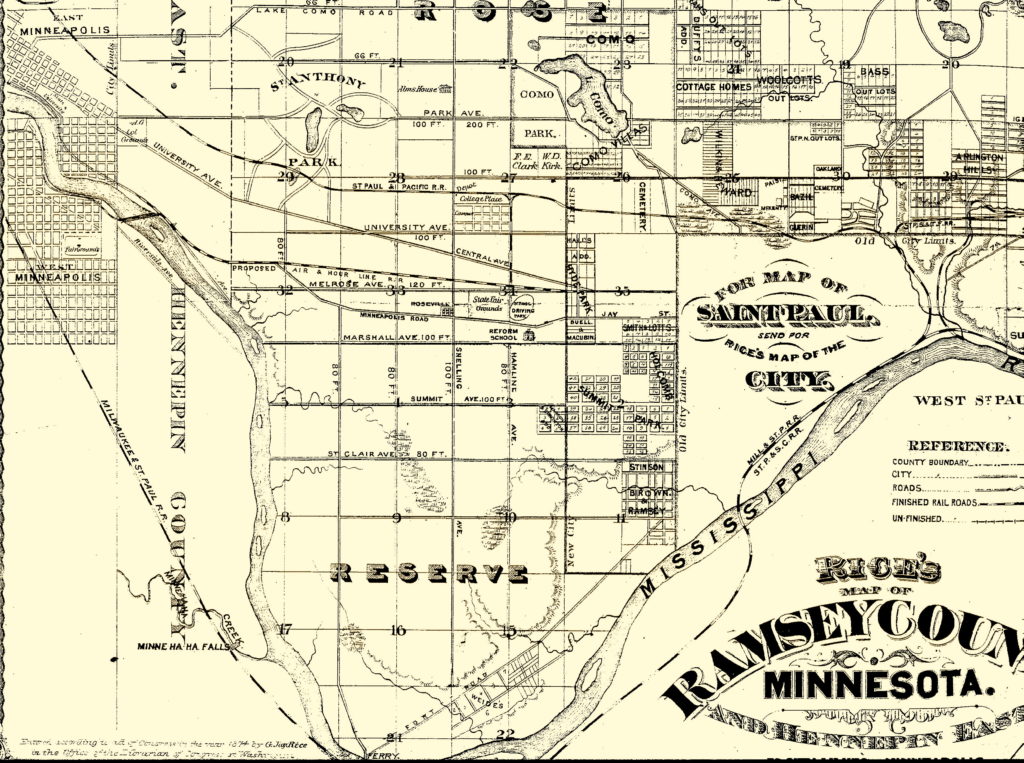

One day in 1940-ish, Jack McLaughlin, age 9 or 10, decided to walk along the railroad tracks. Suddenly he noticed a strange ticking noise from behind him and turned around just in time to see a train sneaking up on him and a conductor who had climbed out onto the front of the locomotive about to tap him on the shoulder.

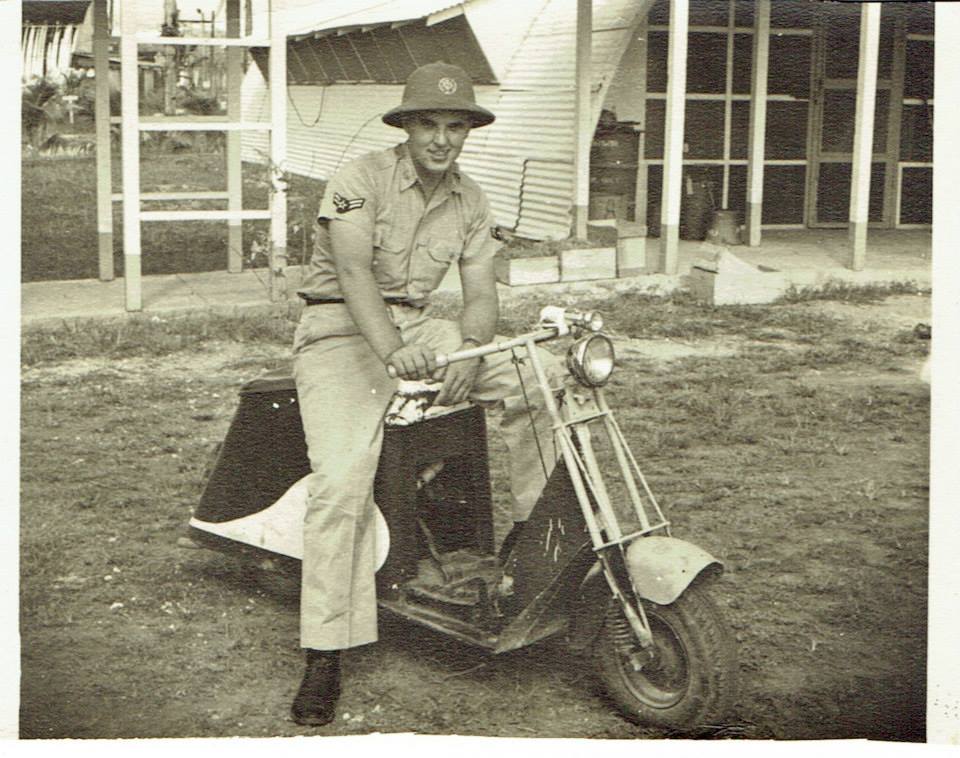

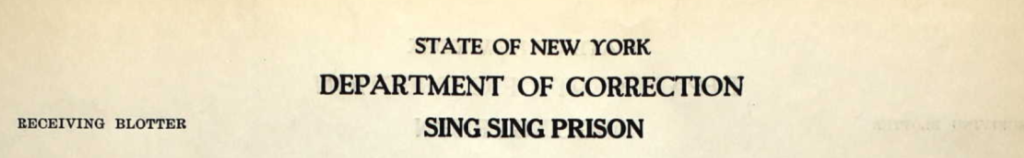

In 1952, Jack enlisted in the Air Force, hoping to become a pilot. He was not allowed to get flight training because he had hay fever, so he became a medic. During the time he was stationed in Alabama, he was not only sent out to administer polio vaccines at local elementary schools, but also administered vaccines to the people on base. On one vaccine day at the base, he overheard an officer blustering at his men for being afraid of needles – so when it came the officer’s turn, Jack turned around with a surprise: a massive spinal needle that had been wound into a corkscrew around a pencil. As I recall the story, the man fainted.

Jack was later stationed on Guam. In addition to telling stories about the extremely large spiders in the barracks, his unit’s pet dog, and the remarkable storms that blew over the island cutting sharp lines of rainfall across the road in front of his perfectly dry Jeep, he also once mentioned encountering a small World War 2 memorial, which consisted of a pile of American GI helmets, each, he carefully noted, with a hole in it.

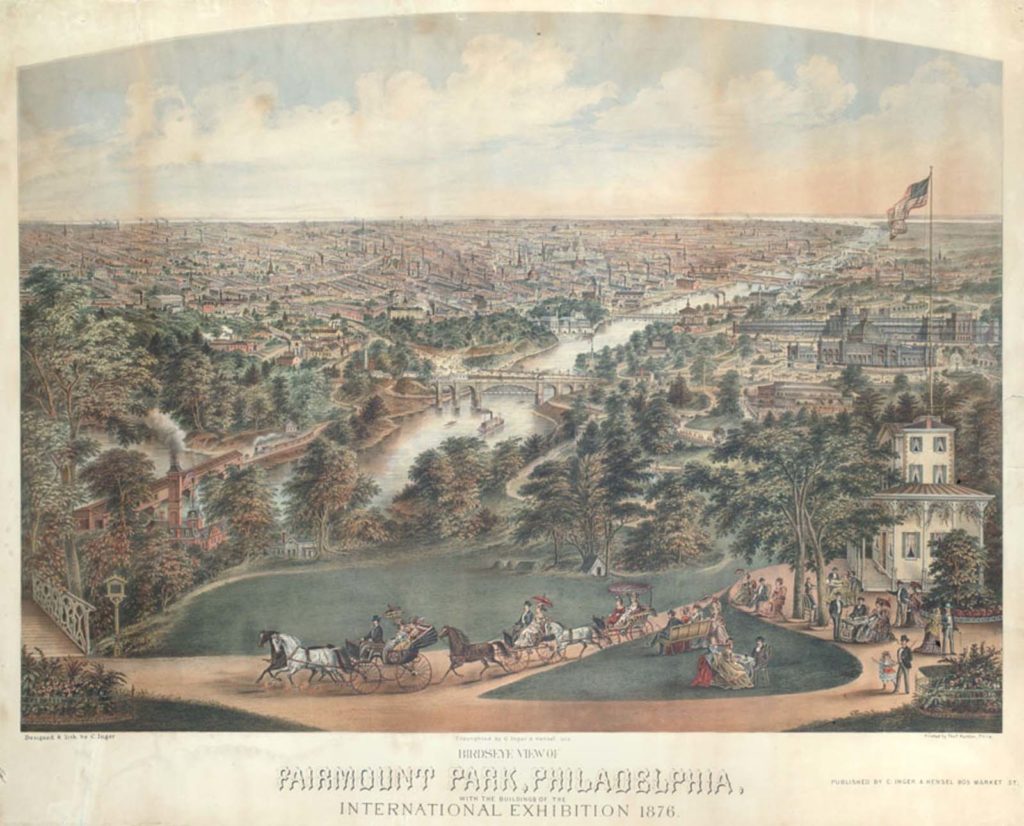

Importantly: in 1963, Jack and Doris got married. They drove down Skyline Drive in the Appalachians to enjoy the autumn colors on their way to their honeymoon in Florida. In Florida, they visited Sea World, where Jack was surprised by a large wet ball smacking him in the chest. When he looked around, the dolphin who had thrown it laughed at him.

In 1968, Jack and Doris became parents. Apparently, during the final stages of Mom’s labor, Dad argued with the doctor about whether I was a girl or a boy. Eventually, to everyone’s – especially Mom’s – relief, I emerged fully into the world, which also settled the argument in the doctor’s favor.

In my early childhood, Dad taught me how to find the North Star and one night woke me up to watch a total lunar eclipse. I’m not sure he was prepared for the onslaught of astronomy that the rest of my childhood brought him, but he rolled with it, taking me to Mount Cuba, getting me a subscription to Sky & Telescope, and doing the research to find the best night to show me the four visible moons of Jupiter with his trusty binoculars.

During the summer between 4th and 5th grade, I wiped out on my bike. The only part of that entire event that I remember clearly was Dad sitting on the couch with me, ever so gently wiping the sand and grit out of the road rash on my face.

As many of you know, Dad and Mom bred and showed Airedale Terriers for some 50 years. While I was involved with caring for the puppies from second grade until I went to college, I most vividly remember the first time we had a puppy not thrive. I have a lasting image of Dad sitting in the dog room, the failing puppy cuddled against his chest in one of his big hands, bottle-nursing the puppy with warmed formula.

Many people know the grooming tools that Dad designed and produced, employing nearly every teenager in our family in that production process over the years. But you may not know about his other engineering accomplishments, such as being involved in the development and testing of Dupont nylon-based products for irrigation and construction, designing other grooming tools that didn’t quite pan out, and building an incredible volcano for my end of year project in 7th grade social studies. The volcano could not be tested because it was a one-shot eruption, but because Dad had an incredible talent for thinking through a project, it erupted perfectly, to the envy of my classmates.

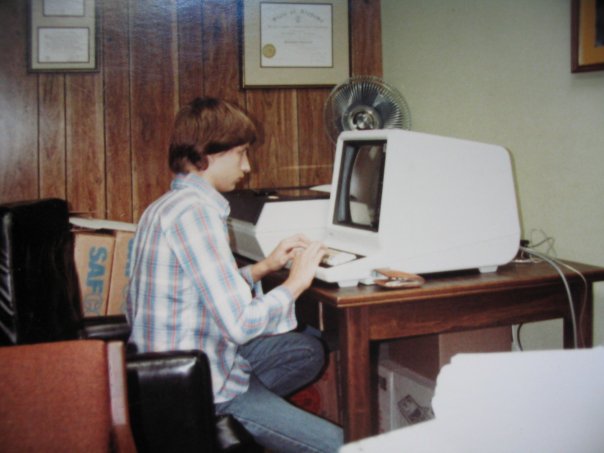

In the early 1980s, Dad introduced me to computers. He was an early adopter of computers of all sorts, got me my first Commodore 64, and encouraged me to take programming classes at a time when I was the only girl in the room. I also had email and computer games before pretty much any of my peers, thanks to Dad.

During my first driving lesson, Dad taught me that it was my responsibility to ensure that my passengers were safe and comfortable at all times in my car. Then one of the tires blew out, and then the skies opened in a drenching deluge. So Dad taught me how to change a tire in the pouring rain, standing in next to me while I did the work. Practical, hands-on training, which oddly came in very handy not too many years later.

Dad became quite the legend to my cousins when they worked for him in the basement workshop. “Uncle Jack is a ninja!” was the way they rationalized his uncanny ability to appear at their elbows when they least expected him. He claimed he never tried to startle anyone, but he always had a pleased little smile when he said it. And then there was the Christmas when he showed Pegeen’s family a rope magic trick, and both the boys spent an hour or more trying to replicate it while the rest of us giggled ourselves sick, and Dad just sat there grinning.

In 2008, Dad had a double heart bypass surgery, and it was a rough recovery for him, in part because he had a heart attack on the table that left him with heart failure. However, after his 6 months of cardiac rehab were over, he joined a gym and continued to go 3 times a week until the pandemic put a stop to his workouts. He reversed his heart failure diagnosis and kept himself going well past the expectations of his cardiologists. He was determined to stay as long as possible for Mom.

Last year, Mom ended up in the hospital and rehab for a month, and Dad and I spent all that time together, making the best of a bad situation. We discussed her care and made all the phone calls and figured out everything we needed – and probably more than we needed – to bring her home safely. We drove into the hinterlands of Bear for medical equipment and went to visit her at least once a day in rehab. But we also talked about our lives. He asked about my job and some of my more colorful employment adventures, and I heard more about his work with Dupont and his time in the service than I ever had before. I’ll always be grateful for that time with him.

I inherited his hair cowlicks, his McLaughlin build, and his big gentle hands. I learned from him the creative knack for solving problems for my friends and family, his ability to pass along knowledge in a number of ways, and the determination to be present for my loved ones no matter what.

I am not the daughter he expected, but I know that his support and love was unwavering. He always told me that I could do anything I wanted to do. And he was right, as he often was.

My father was my most steadfast rock, as I know he was for Mom, and my greatest example of generosity and kindness. He gave me the moon and the stars, and stories upon stories upon stories.

One of my favorite authors, Sir Terry Pratchett, wrote, “Do you not know that a man is not dead while his name is still spoken?” Today, I would ask you all: tell the Jack stories. Pass on the things he taught you, with attribution. Gift forward his dad jokes and his immense generosity, his trickster games and his deep sense of wonder, his sense of responsibility and his abiding, if occasionally curmudgeonly, love.

Ad astra, Dad. To the stars. I love you.