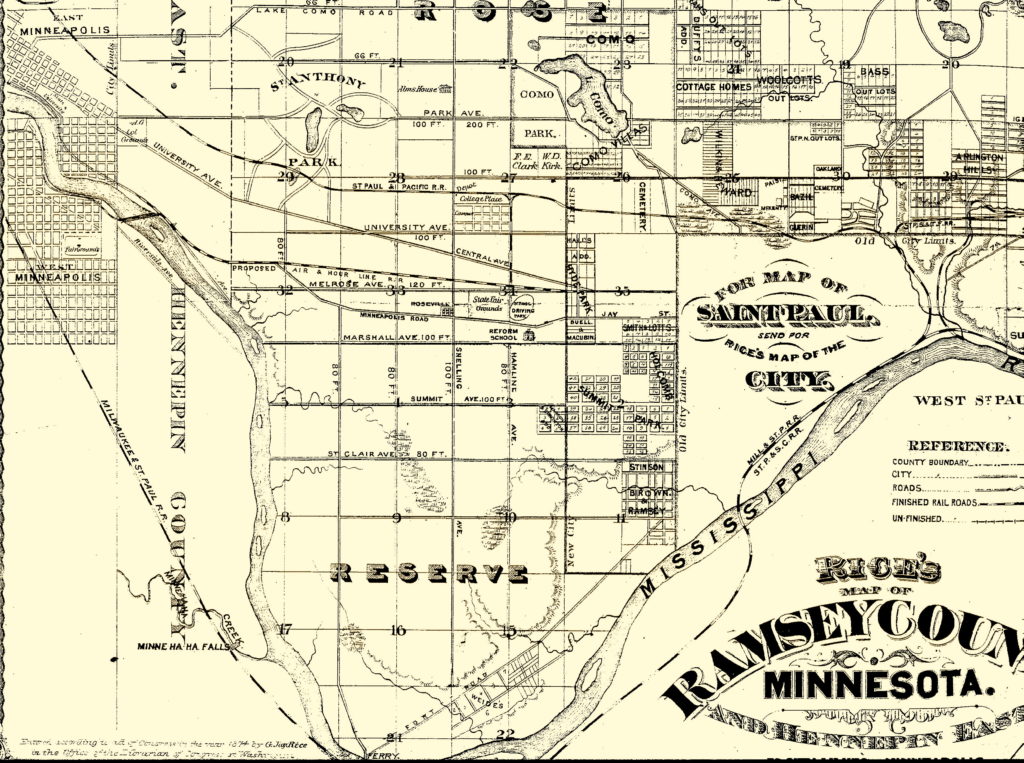

Mary Naughton was born around 1867 in Minnesota, the eldest girl in a group of 8 siblings, 5 of whom survived to adulthood. Their father died in 1875 at age 44, and the youngest child of the family was born posthumously in February 1876. The oldest boy went to work as a messenger and telegraph operator by the time he was 15, and eventually took up as a carpenter/roofer around 1883, before dying very young in 1890. Mary started working in 1884 as a clerk, and eventually began working as a print compositor at Graphic Illustrating Company and then the West St. Paul Times around 1894, where she stayed until at least 1899. Her remaining brothers all scattered out of the house, and her only sister entered a convent around 1894.

Mary worked as a clerk (where was unspecified in the city directory) from 1902 to 1904, when her mother died. Her mother’s will specified that she should have a room in the house that was willed to her younger brother, and she was still living there in 1905. But then in 1906, she vanished. Under normal conditions, I would have assumed that she married and Ancestry’s algorithm couldn’t connect her to her married name.

But then something odd happened: a Mary Naughton, same birth year and born in Minnesota, appeared in Colorado Springs, Colorado, working as a print compositor.

She was listed in the Colorado Springs directory in 1909 and 1910 as a printer for the Manitou Journal. In 1911, she was listed as a clerk, but from 1912 through 1916, she was listed as a printer or a compositor for the Manitou Springs Journal.

Manitou Springs, and Colorado Springs in general, was a medical destination, known for its mineral waters and crisp, clean, mountain air, both of which were prescribed as treatments for patients with tuberculosis. By 1900, apparently, about a third of the population in the area were patients there for treatment. It does raise the question as to why Mary chose Manitou Springs as her new home — did she have tuberculosis? Was she simply well enough to keep working?

Mary lived at 147 Deer Path Ave until 1914 (it looks like most of the local houses there are more modern now), then moved to Capitol Hill near Montcalm Sanitorium in 1915 and 1916.

This is a fascinating area of the town. The original Montcalm Sanitarium was built near the Miramont Castle, a building constructed as a private residence by Father Jean Baptiste Francolon. According to this website, “Francolon was from France, and had lived in several countries as a diplomat’s son. It’s believed that the priest chose architectural styles that he liked from those countries. He designed his 1885 [sic, other sources say 1895] 30-room castle in nine architecture styles: shingle-style Queen Anne, English Tudor, domestic Elizabethan, Romanesque, Flemish stepped gables, Venetian Ogree, Byzantine, Moorish and half-timber Chateau. The castle has hidden compartments and tunnels and is built against a mountain, secured to the mountain by huge bolts.”

Per this article, Francolon and his mother built an earlier house next to where they later built the castle, and donated that house to the Sister of Mercy to become a tuberculosis sanitarium (Montcalm). He apparently built both places with his mother’s money (she was the daughter of a French count), and his parishioners didn’t like that he came from wealth. The mother superior of the Sisters of Mercy accused him of molesting children, and a lynch mob drove Francolon out of town ca 1900. His mother returned to France a few months later.

The Sisters began to move their sanitarium into the vacant Miramont around 1904, and completed the move when the original sanitarium burnt down in 1907. So by the time Mary moved there, the Castle was well and truly established as a health destination. The houses along Capitol Hill Avenue appear to have been built by and large in the late 1880s and 1890s, and at least some were probably boarding houses.

The last time I could find her in the city directory was 1916, when she was 49. I was disappointed that there were no death records available for the area.

But then a Mary Elaine Naughton appears in Colorado Springs, marrying an optometrist named Eugene D McC— on December 22, 1920. According to their marriage license, they were both living in Cook County, Illinois, (presumably Chicago) at the time, and I guess decided to elope to Colorado Springs.

My speculation ran wild at this point: was this Mary, who having perhaps run off to do war work, landed in Chicago, fell in love, and eloped back to her favorite place?

The couple appears to have stopped there on their way to Los Angeles, where they settled down. In 1921, they had one child, Eugene D Jr. This did give me pause: she would have been in her early 50s at that point, even if her birth year was a little wobbly in the way of census records. But weirder things have happened. Or they could have adopted.

The family appears in the 1930 and 1940 censuses, and there was another clue that this might not be my Mary: her birth year was slotted into the 1890s. Could she possibly lie about her age to that extent? I’ve seen several examples of people (not just women) munging their age about on census records, my grandfather among them, but not usually more than about 10 years. My gut was saying no, but my brain was still chasing down the rabbit hole.

Eugene Jr, an optometrist like his dad, married a woman who sounded utterly lovely, who had performed with Sonia Henie and Esther Williams. They had one son, who got a full football scholarship to Stanford. He’s now a guitar player based out of Texas.

Around the time I found him and dropped him email to see if I could make a connection, I found Mary and her Eugene traveling back from Mexico in 1933, and all my hopes fell over with a thud. Mary was listed as being born in Chicago on May 26, 1898.

I followed the rabbit hole to the conclusion: Eugene Sr apparently died of a coronary thrombosis while staying at the Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas on November 24, 1956, age 67. According to his brief obituary, he was on vacation. Mary appears to have died in 1965, and her gravestone seems to indicate that she was 67 or 68 years old. And then I received the final nail in the wild speculation: email from this Mary’s grandson, indicating that she was most definitely from Chicago, not the Twin Cities.

So I’m back to 1916 and the mysterious disappearance of Mary Naughton, originally of St Paul, Minnesota. The logical conclusion here is that she probably died. Perhaps she went to Manitou Springs originally because she had tuberculosis, as I speculated earlier, and while she was well enough for several years to work, it finally caught up with her. Maybe she ended up in one of the local sanitariums, perhaps even Montcalm.

My lesson here is to listen to my gut when it tells me that I’m going down a wrong path, no matter how attractive having a solution may be. I can apply my critical gut instinct to other people’s family trees (especially all those that are like “oh look we’re related to a Scottish laird/British nobility with no documentation at all!”), and I need to make sure I’m bringing that same critical thinking to my own trees.